Biophilia and Design

Written by Judith Heerwagen, GSA's Office of Federal High-Performance Buildings

Imagine you went to sleep one night after an evening spent outdoors in your backyard, enjoying the sights and sounds of a garden lush with trees, plants, butterflies, hummingbirds sipping nectar from the flowers, a well-used birdbath, and welcomed shade on a warm summer night.

When you wake up the next day and head to the garden to enjoy your morning coffee, you are alarmed to see the lush garden and its animal visitors are all gone, replaced by dead grass. How would you feel? After the initial shock, you would likely feel distressed – as if you had lost something of huge emotional value that may not be retrievable.

Although this is an imaginary scenario, it is an increasing possibility for people across the globe as we experience the potential consequences of climate change. Forest fires, droughts, floods, and temperatures well into the 100’s are increasingly common. Nature is under siege, leading to increasing negative consequences for life and health of both humans and other living species. Biophilic design aims to reconnect people with nature in ways that support both human and biological health in the built environment.

Case Study

The Importance of Daylight

While many people prefer to be in spaces with abundant daylight, a critical question is to what extent the benefits of daylight matter to those who spend the majority of their time indoors, particularly in an office setting.

Origins

The term “biophilia” was first used by psychoanalyst Eric Fromm who argued that humanity needed to establish a non-destructive relationship with the natural environment by fostering a love of living beings – which he called “biophilia.” Without this love of nature, humanity would see increased pollution of air, water, soil, and animals (Fromm, 1973).

In his 1984 book, Biophilia, E.O.Wilson describes biophilia from an evolutionary perspective: “To explore and affiliate with life is a deep and complicated process in mental development. To an extent still undervalued in philosophy and religion, our existence depends on this propensity, our spirit is woven from it, hope rises on its currents."

If there is an evolutionary basis for biophilia, as asserted by Wilson, then contact with nature is a basic human need, not a cultural amenity, not an individual preference, but a primary need. Just as we need healthy food and regular exercise to flourish, we may need on-going connections with the natural world. Wilson also saw biophilia as a natural force that could be used to combat worldwide loss of biodiversity. If we love nature enough, we will be willing to save it from destruction. A significant body of research tells us that, as a species, we are still powerfully responsive to nature’s spaces, forms, sounds, and patterns (Kellert, Heerwagen and Mador, 2008). Unfortunately, the benefits from regular contact with nature are under threat due to climate change and its impact on natural systems. This situation has created a growing sense of urgency that leads us to seek out nature as a source of health and resilience in the face of adversity.

Theoretical Perspectives

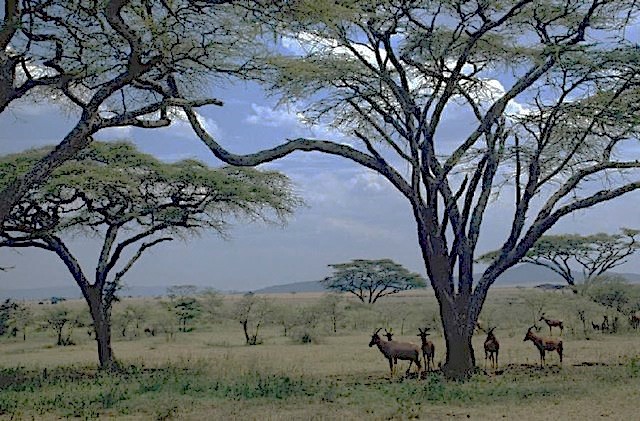

To understand the deep underpinnings of biophilia and its manifestation in today’s cultural and physical landscape, we need to start with our ancestral life as mobile hunting and gathering bands on the African savannahs. Buildings are newcomers on the evolutionary scene – a mere 6,000 or so years old. For most of human existence, the natural landscape provided the resources necessary for survival, chief among them water, vegetation, sunlight, animals, building materials, shelter, sky, and fire. The sun provided warmth and light. The big sky provided information about weather and time of day that was critical to wayfinding and safety. Large trees provided shelter from the midday sun and places to sleep at night to avoid terrestrial predators. Flowers and seasonal vegetation provided food, materials, and medicinal treatments. Rivers and watering holes provided the foundation for life itself – drinkable water.

Translating Theory into Practice

Discussions of biophilic design focus on built and natural features that create a sense of pleasure and enjoyment, such as the interplay of elements such as prospect and refuge as well as the use of daylight, views, water, and plants. Less attention is paid to ephemeral characteristics of space that derive from nature. These features, identified below, can add interest and a sense of aliveness to built spaces. Research on these topics is also summarized below to provide context for the array of nature experiences that influence human functioning.

A range of natural elements and features are important to the human experience of biophilic environments whether they are indoors or outdoors. These factors include water, large trees, flowers, rich vegetation, natural patterns, and natural systems. We also know that certain spatial characteristics of natural environments have strong appeal, such as views to the horizon, provision of refuge, and a sense of enticement that invites exploration.

Natural environments also have many sensory qualities and compositional features. Design can evoke the qualities, relationships, and structures of nature without direct replication. This approach is widely relevant to design, and especially to buildings in urban areas that lack natural amenities. The ideas are scalable and can be applied at the room, building, and landscape levels.

Biophilic Design Principles and Goals

Our fascination with nature is derived from the qualities, attributes and experiences of natural settings that we find particularly appealing and aesthetically pleasing. The goal of biophilic design is to create places imbued with these features that promote positive emotional experiences -- enjoyment, pleasure, interest, fascination, and wonder -- that are the precursors of human attachment to and caring for place.

Those who can afford to do so live near parks, have large street trees, rich landscaping around their homes and they work in places that have design amenities. However, as the section below shows, there are many ways to incorporate biophilic design features throughout the urban built fabric. While living nature is always highly desirable, it is possible to design with the qualities and features of nature in mind thereby creating a more naturally evocative space. Design imagination can create many pleasing options out of this biophilic template.

Using knowledge of our affinity for nature can benefit the environments we create. Work environments can become both more relaxed and productive, homes more harmonious, and public space more inclusive, offering a sense of belonging, security and celebration to a wider cross-section of people. We also need to acknowledge that nature is not always pleasing. Hazards abound and are often made worse by human behavior. Pandemics, fires, floods, draught, and excessive heat experienced across the globe, are witness to human-influenced climate change leading to widespread destruction of natural environments and loss of both human and animal lives. This makes the need for a healthy natural environment - and its integration with the built environment - even stronger and more urgent.

How Do We Know Biophilia Enhances Health?

Interest in biophilia within both the research and design communities has grown rapidly since E.O. Wilson’s 1984 book on biophilia. A 2018 Google search on the term “biophilia” provided 1,760,000 hits while “biophilic design” produced 619,000 hits. Not surprisingly, research on the topic has also grown considerably, especially on the human benefits of connection to nature, and more recently, on issues of how urban biophilia can help mitigate climate change while also supporting public health goals.

This section provides an overview of key findings on the links between human health resulting from a variety of biophilic applications – from indoor vegetation and daylight to window views and water features. The focus is primarily on biophilia in the built environment.

Due to the extensive body of research on biophilia, this section is intended to identify key findings relevant to building design rather than to provide a detailed review. Recent reviews are identified in the bibliography for those wanting more information.

Table 1. Links Between Biophilic Elements and Health Outcomes

| Design Element | Stress Reduction | Enhanced Mood | Improved Cognitive Performance | Enhanced Social Engagement | Enhanced Sleep | Enhanced Movement |

| Indoor Plants | X | X | X | |||

| Fish tanks | X | X | ||||

| Flowers | X | |||||

| Water | X | X | ||||

| Views and images of nature | X | X | ||||

| Daylight & circadian effective light | X | X | X | |||

| Thermal transitions | X | |||||

| Outdoor green space | X | X | X | |||

| Varied spatial environment | X | X | ||||

| Green roofs | X | X | ||||

| Natural, fractal patterns | X |

Daylight Reduces Stress, Improves Cognitive Function, and Helps Sleep

In addition to creating a visually pleasant environment, indoor daylight can also enhance mood, improve cognitive functioning, reduce stress, and reduce the use of strong pain medicine in hospital settings.

Window Views Matter - Especially Views of Nature

While much research on windows has focused on reduction of glare and heat gain, the health benefits of views is an active area of research. Results show that views of trees and vegetation reduce stress, enhance mood, improve the recovery process in hospitals, and enhance cognitive performance in work settings compared to views lacking natural features.

Indoor Plants have Physiological and Psychological Benefits

Plants have long been used to enhance the appearance of indoor spaces. Research on the benefits of plants also shows reduced respiratory symptoms likely linked to improved air quality. In addition to green plants, flowers are also associated with positive outcomes, especially increases in positive emotional functioning.

Visual Displays of Nature Enhance Health and Well Being

Health benefits can also be achieved indirectly through the use of photos or videos of nature. Research shows both physiological and psychological responses to nature versus urban scenes. The findings show strong support for more positive benefits with nature-based visual stimuli.

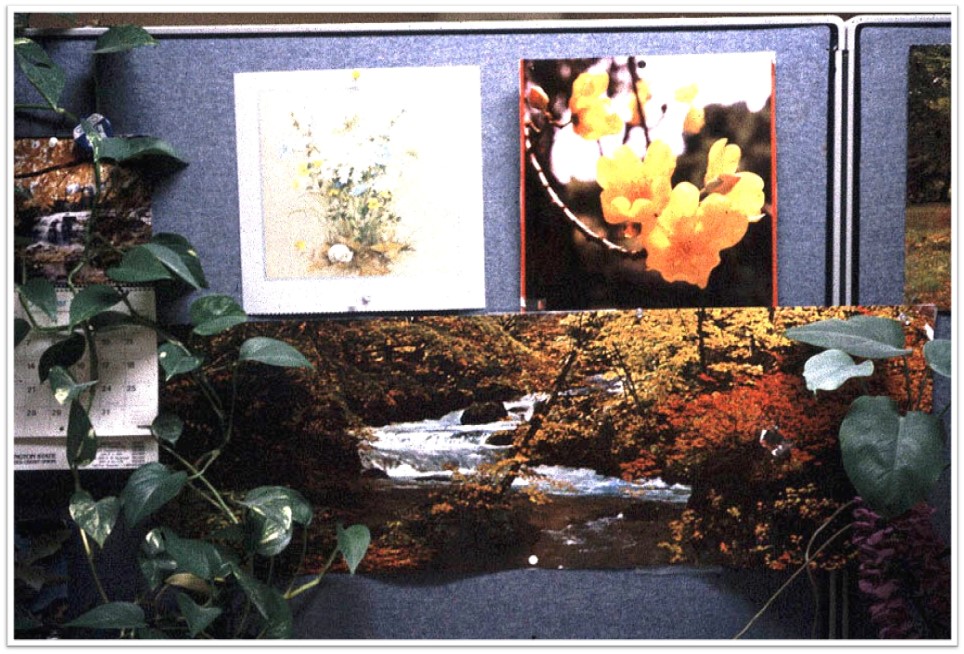

People in Windowless Spaces Enhance Their Well Being with Nature Images

Although people have a strong preference for working in spaces that have windows, there are many windowless work environments. Research shows that people in such spaces often decorate their workspaces with nature posters or plants, perhaps as a way to compensate for lack of connection to the outdoors.

The Psychological Value of Water

Given its importance to human life, studies on the health benefits of water are surprisingly scarce compared to the extensive research on water-borne health problems. However, researchers have begun to focus on the qualities of water that influence people’s preferences. A review of human responses to a variety of water features (referred to as “blue space”) concludes that water is clearly a component of preferred landscapes.15

Prospect and Refuge

Landscape design intuitively uses prospect (long distance views) and refuge (places of protection), with multiple long distant views often to the horizon, coupled with subspaces that offer protection and hiding.

The co-occurrence of prospect seems to be so obvious that research on the topic is scarce. However, one compelling study of human response to landscape scenes shows that those with both long distance views and places of refuge stimulate the opioid centers of the brain, creating a sense of relaxed enjoyment that may encourage movement and exploration.18

Non-Visual Sensory Systems

Environmental experience is multi sensory, not just visual. Yet less attention has been paid to other sensory systems in biophilia research. However, research in other fields such as acoustics and thermal comfort address conditions relevant to biophilia.

For example, recent work on sound looks at the health impact of soft nature sounds (birds, water, breezes) versus annoying sounds such as traffic, construction work, and people talking on cell phones.19 The authors conclude that quiet sounds linked to nature are indicative of safety and thus reduce stress and restore attentional capabilities allowing for high level cognitive functioning, including creativity. Louder, annoying sounds are more indicative of danger, and thus narrow attentional scope to focus on dealing with the danger.

Other researchers are exploring how thermal transitions can create momentary pleasure and result in greater satisfaction overall than constant indoor temperature conditions.20 Whether such transitions could also create a sense of pleasure for other sensory stems is not known. However, the high variability in natural light across the day suggests that more indoor variability – especially in windowless environments – could generate feelings of pleasure.

Overall summary of Research Findings

Research on biophilia shows that many different elements of nature, from daylight to plants and flowers, have consistent positive benefits on human health and well point to positive outcomes linked to attention restoration and stress reduction – both of which can enable more focus and greater use of executive functions associated with more complex cognitive performance.

Key conclusions from this research, as summarized in a review by Beute and de Kort are:21

- Biophilic benefits have validated pathways of impact - including psychological mechanisms (preference, psychological stress reduction, emotional functioning, cognitive processes, and to a lesser extent social behavior) and physiological mechanisms (circadian entrainment, serotonin production, alertness, and physiological stress reduction).

- The aspects of nature associated with these outcomes are consistent across diverse research projects and include large trees, plants, distant views, refuge, sunlight, and water.

Implementing Biophilic Design

Biophilic design translates our evolved propensity to affiliate with nature into strategies for improving health, well-being, and performance in the built environment. The brief review above shows that biophilic features have numerous positive benefits including stress reduction, enhanced emotional functioning, improved cognitive performance, social engagement, and better sleep.

In addition to elements and spaces that enhance experience of place, it’s important to also avoid spaces associated with danger or illness – a condition often referred to as “biophobia” because of the unease and stress associated with being in a space that can harm rather than heal. Like biophilia, the sense of biophobia is considered an evolved response intended to elicit avoidance or escape behaviors.

Features associated with biophobia include:

- Darkness

- Loud or uncontrollable noise

- Unkempt or hazardous spaces

- Presence of vermin and/or unpleasant odors

- Dead or dying plants due to lack of care

- Poor wayfinding leading to feeling trapped or lost

The Biophilic Design Continuum

One way to think about biophilic design is to see it as a continuum as shown below. As one moves from a biophobic to a biophilic space, there is an in-between space (bio-indifference) that eliminates the negative aspects of biophobia, but does not contain the natural features and attributes that promote health. Many current building spaces are likely to fall in the “bio-indifference” category where harmful elements are largely eliminated, but health-enhancing benefits are not present. An infographic from the Washington Post![]() illustrates the concept.

illustrates the concept.

Table 2. The Biophilic Design Continuum

| Biophobia | Bio-Indifference | Biophilia | |||

| Factors associated with the biophilic design continuum |

|

|

|

||

| Health & well-being consequences |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|||

|

Dark hallways

|

High Partitions

|

Hallway with lights and plants

|

Table 3 below summarizes the components of biophilic design in terms of specific elements, natural attributes, and spatial patterns. This is just one way to characterize biophilia. Others categorization schemes and practice approaches are presented in the 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design by Terrapin Bright Green19 and in The Practice of Biophilic Design by Stephen Kellert and Elizabeth Calabrese.20

Table 3. Components of Biophilic Design

| Component | Examples |

|---|---|

| Natural Elements | |

| Living nature | Trees, flowers, water and animals in the form of green walls, potted plants, and fish tanks or koi ponds. |

| Connection to nature can be through nearby outdoor spaces, window views or indoor applications. | |

| Natural materials | Wood and stone increase the appeal of a space and provide visual and haptic variability. |

| Life-like elements | Life-like elements include light, sky, fire and water. The term “life like” refers to the capacity for these elements to change over time and to be present in different forms. |

| Natural Attributes | |

| Sensory variability | Sensory variability includes variation in sounds, light, color, temperature and air movement across spaces and time. |

| Patterned complexity | Patterned complexity (“rhyming”) includes elements that vary, yet have an organizing theme (such as a flower garden). |

| Fractal patterns | Fractal patterns are common in nature (trees, rivers, wood) and can be used as décor in a variety of ways (carpet, wall hangings, paintings). |

| Spatial Relationships | |

| Prospect | Prospect can be achieved in many ways including internal and external views and view corridors; variation in view types and content (e.g., views of human activity or nature spaces), daylight, atria, wall wash lighting, viewing platforms (decks, terraces, balconies), use of mirrors to give the illusion of spaciousness. |

| Refuge | Refuge is illustrated by enclosure and sensory retreat using overhead canopies and vertical screening; balconies that provide both views and ability to stay in a darker area. |

| Enticement | Enticement such as curvilinear surfaces gradually open information to view and provide motivation to move and explore. |

Using the Biophilic Design Elements

The most biophilic buildings incorporate multiple features that are revealed in the building façade, lobby, interior design, and surrounding landscape. The intent is to create an interior habitat of features that go together in a harmonious way drawing on the features and attributes of the climate and landscape where the building is located.

A biophilic design does not need to contain all of the desired elements and attributes, but rather the components that make the most sense given the context – which, in addition to climate and landscape, include the building purpose (office vs hospital), the organizational culture and mission, and occupant needs and characteristics.

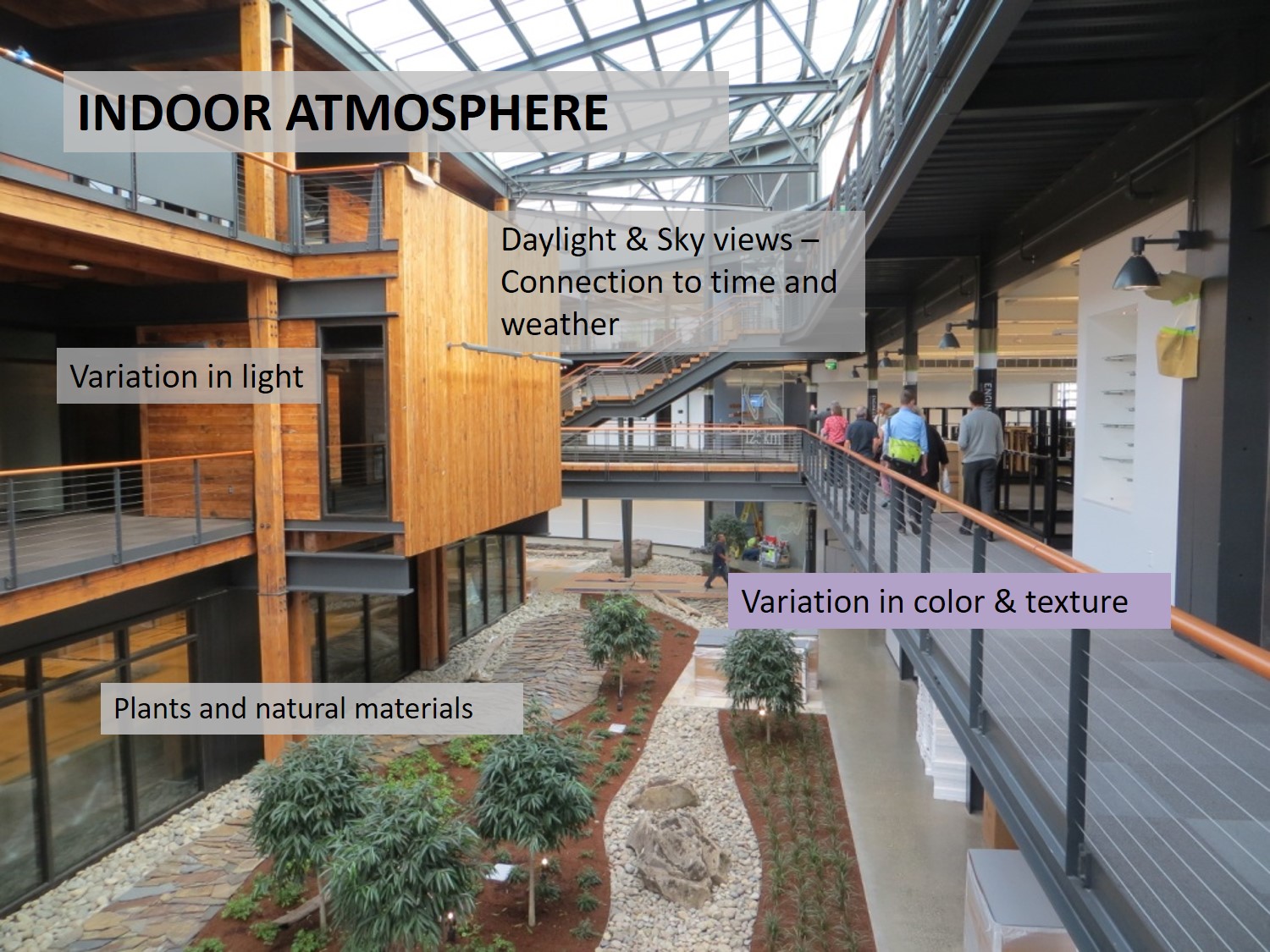

Federal Center South, Seattle

The new Federal Center South building in Seattle exemplifies an approach to biophilic design that links sustainability, organizational mission, and connection to nature indoors and outside. The building houses the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

Biophilia was used as a framework for the overall design. The design includes expansive views across the building and to the outdoor landscape in all directions, an interior atrium with a meandering riverbed of rocks and plants, views to the Duamish River, extensive indoor daylight, and use of recycled wood for the interior walls. The building also has a well developed and balanced approach to prospect and refuge that includes open interior views coupled with numerous places for refuge without feeling totally enclosed.

Federal Center South received a LEED Platinum rating for its sustainable design and received the American Institute of Architects COTE award and COTE+ award for its stewardship of the environment.

Concluding Remarks

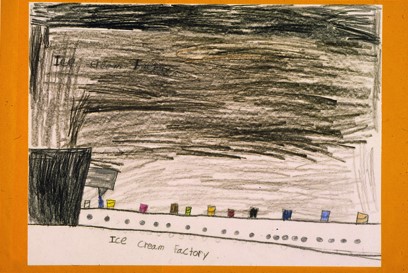

The research on biophilic benefits cited in this article come almost exclusively from adult populations. It is worth stepping back a bit and asking what would children say? The two images below come from children who were visiting a Herman Miller manufacturing plant in Holland, Michigan. Before the visit to the building, the teacher asked them to draw a picture of a factory. The photo on the left was typical of the drawings – they looked grim and dark. Hardly an exciting place to work. After the tour, when the children returned to class , the teacher asked them to draw another picture. The one shown here has happy people and the interior street lined with plants and wooden animals, including a snake and giraffe. Clearly, the experience had a powerful, positive emotional effect.

|

|

|

|

Children's factory drawing

|

Children's factory drawing after visit to Herman Miller Building

|

Additional Suggested Readings

- Appleton, J. 1977. The Experience of Landscape. London and New York: Wiley.

- Browning, W, Ryan, C. and Clancy, J. 2014. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design

. Terrapin Bright Green LLC.

. Terrapin Bright Green LLC. - Gillis, K. and Gatersleben, B. 2015. A review of psychological literature on the health and well being benefits of biophilic design. Buildings, 5: 948-963.

- International Living Future Institute

- Kellert, SR. 2018. Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Kellert, SR and Calabresse, EF. 2015. The Practice of Biophilic Design

. Biophilic-design.com

. Biophilic-design.com - Kellert, SR, Heerwagen, J and Mador, M. 2008. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. New York: Wiley.

- Sturgeon, A. 2018. Creating Biophilic Buildings. Ecotone Publishing.

- Wilson, E.O. 1984. Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

1 Orians, GH. 1980. Habitat selection: general theory and applications to human behavior. In J.S. Lockard (Ed) The Evolution of Human Social Behavior. Chicago: Elsevier 2 Appleton, J. 1975. The Experience of Landscape. New York: Wiley. 3 Walch, J.M., B.S. Rabin, R. Day, J. Williams, K. Choi, J.D. Kang, 2005. The effect of sunlight in postoperative analgesic medication use: a prospective study of patients undergoing spinal surgery. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67(1): 156-163. 4 Figueiro, M., B. Steverson, J. Heerwagen, K.Kampschroer, C.M. Hunter, K. Gonzales, B. Plitnick, and M.S. Rea, 2017. The impact of daytime light exposures on sleep and mood in office workers. Sleep Health, 3: 204-215. 5 Urlich, R.S., 1984. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224:420-421. 6 Heschong, L., D. Aumann, N.Jenkins, T.Suries and R.L. Therkelsen, 2003. Windows and offices: a study of worker performance and the indoor environment. California Energy Commission, 1-5. 7 Kaplan R. 1983. The role of nature in the urban context. In .Altman and J.F. Wohlwill (Eds) Behavior and the Natural Environment. New York: Plenum. 8 Fjeld, T., B. Veiersted, L. Sandvik, G. Rilse, and F Levy, 1998. The effects of indoor foliage plants on health and discomfort symptoms among office workers. Indoor Built Environment. 7:204-209. 9 Haviland-Jones, J., H.H., Rosario, F, Wilson, P. and T. McGuire, 2005/ An environmental approach to positive emotion: flowers. Environmental Psychology, 3:104-132. 10 Orians, G.H. and Heerwagen, J.H. 1992. In J.H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, and J.Tooby (Eds). The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture. New York and Oxford, University of Oxford Press. 11 Ulrich, R.S. 1993. Biophilia, Biophobia and Natural Landscapes. In S.R. Kellert and E.O.Wilson, Eds. The Biophilia Hypothesis. Washington DC: Island Press, Shearwater Books. 12 Ulrich, R.S., 1990. Effects of nature and abstract pictures on recovery from open heart surgery, Congress of Behavioral Medicine, Uppsala, Sweden. 13 Heerwagen, J.H. and Orians, G.H, 1986. Adaptations to windowlessness: A study of the use of visual décor in windowed and windowless offices. Environment and Behavior,18(5): 623-629. 14 Bringslimark, T, Hartig, T. and Patil, G.2011. Adaptation to windowlessness: do office workers compensate for a lack of visual access to the outdoors? Environment and Behavior 43(4): 469-487. 15 Volker, J. and Kistemann, T., 2011. The human impact of blue space on human health and well being: the salutogenic health effects of inland surface waters: a review. Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 214 (6): 449-460. 16 Mador, M. 2008. Water, Biophilic Design and the Built Environment. In S.R.Kellert, J.H. Heerwagen, and M. Mador (Eds.) Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. New York: Wiley. 17 Coss, R.G and Moore, M.1990. All that glistens: water connotations in surface finishes. Ecological Psychology, 2(4): 367-380. 18 Biederman,I and Vessel, E.A. 2006. Perceptual Pleasure and the Brain. American Scientist,248-255. 19 Alvaarsson, J.J., Wiens, S., and Nilsson, M.E., 2010. Stress recovery during exposures to nature sound and environmental noise. International Journal of Research in Public Health, 7:1036-1046. 20 Parkinson, T., deDear, R, and Candido, C. 2012. Perception of transient thermal environments: pleasure and alliesthesia, Proceedings of the 7th Windsor Conference, The Changing Context of Comfort in an Unpredictable World. Windsor, UK, April 12-15, 2012. 21 Beute, F. and deKort, Y.A. , 2014. Salutogenic effects of the environment: A review of health protective effects of nature and daylight. Applied Psychological: Health and Well Being, 6(1):67-90.

Related Topics

Biophilia

Biophilia addresses the human attraction to and desire to be in environments that have natural features including parks, gardens, street trees, bird feeders, flowers, big sky, and water elements. Decades of research show that affiliation with nature, whether outside or indoors, can enhance our physical, social and emotional health and boost performance.

Read more about Biophilia and Biophilic Design.

Biophilic Design

Biophilic design aims to reconnect people with nature in ways that support both human and biological health in the built environment.

Read more about Biophilia and Biophilic Design.

Healthy Buildings

Health, as defined by World Health Organization in its 1948 constitution, is “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. This definition of health has been expanded in recent years to include (1) resilience and the ability to cope with health problems and (2) the capacity to return to an equilibrium state after health challenges.

These three health domains - physical, psychological, and social - are not mutually exclusive but rather interact to create a sense of health that changes over time and place. The challenge for building design and operations is to identify cost-effective ways to eliminate health risks while also providing positive physical, psychological, and social supports as well as coping resources.

Learn more about Buildings and Health.