The resource impacted greatest from indoor environmental quality is not energy, water, or physical materials themselves; it’s the occupants that live in and utilize the space. IEQ is composed of more than just indoor air quality (IAQ); acoustics, illumination, thermal comfort, and the ability to control surrounding environmental conditions to personal preferences also impact how occupant interact with the built environment. Optimizing these components can lead to significant benefits for the world’s most valuable resource: people. To discover how IEQ impacts human health and comfort see the Human Impacts section.

Building materials, such as paints, sealants, adhesives, office equipment and furnishings, can emit invisible, odorous, and potentially harmful gasses, such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) or formaldehyde, through off-gassing. VOCs are a class of chemicals that evaporate into the air at ambient (room) temperature and can cause eye, skin and throat irritation among other health complications. Formaldehyde, a human carcinogen from resins used to make wood composite materials, and VOCs should be limited in the office environment to the greatest extent possible. The Explore Section's Spaces include information on low-emitting alternative building materials and the EPA has guidance regarding VOCs and low-emission product labeling.

Ventilation is the process of "changing" or replacing air in any space to remove airborne contaminants such as moisture, odors, emissions from building products and materials (e.g. VOCs and formaldehyde), combustion byproducts, dust, airborne bacteria, and carbon dioxide; and to replenish oxygen. See the HVAC System for more information on the benefits of various ventilation strategies. When using natural ventilation approaches, they must be carefully designed and maintained to ensure they do not negatively affect occupant satisfaction or indoor air quality and are appropriate given local environmental conditions. See ASHRAE’s IAQ Guide for more detailed information on HVAC selection for IAQ.

Visit the Enhancing Health with Indoor Air page to learn more about ventilation and filtration.

Source: Berkeley Center for the Built Environment

Source: Berkeley Center for the Built Environment

Research has shown that environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), or secondhand smoke, from cigarettes, pipes, and cigars has cancer-causing airborne particulates that can cause detrimental health effects when inhaled.1 Smoking should be banned from within the building and nearby (25-50 feet) of building openings such as entries, outdoor air intakes and operable windows. Buildings can also install separate HVAC systems to isolate smoking areas within the facility, although it’s typically uncommon and expensive in the office setting.

1. EPA | Setting the Record Straight: Secondhand Smoke is a Preventable Health Risk

Construction and renovation projects pose a unique threat to indoor air quality. IAQ management plans should be instated that emphasize the protection of building materials from moisture damage and direct the performance of a flush-out procedure to rid stagnant pollutants from the space after construction is complete. Flush-out requires constant circulation of clean outdoor air for a period of time prior to occupancy. During construction or renovation, caution should be taken to limit construction worker and building occupant exposure to potentially harmful airborne pollutants that may be generated by the construction activity, such as dust, lead, and asbestos.

It is no surprise that regular upkeep is necessary to maintain a high indoor air quality, as dust, dirt, and mold accrue on materials in the space over time. Space cleanliness is a large component of IEQ. Employing a green cleaning plan is important in ensuring minimum occupant exposure to airborne particulate matter, along with HVAC filtration and entryway dirt capture systems that eliminate the pollutant source. Discover more on Green Cleaning and Integrated Pest Management in the O&M Impacts section.

Acoustic ceiling tiles, carpeting, furniture finishes, curtains and hanging acoustical plasters can be implemented to mitigate the distribution of sound in the space. Absorption technologies block sound transmission from one space to another and require a relatively low financial investment. Choose materials with a high noise reduction coefficient (NRC).

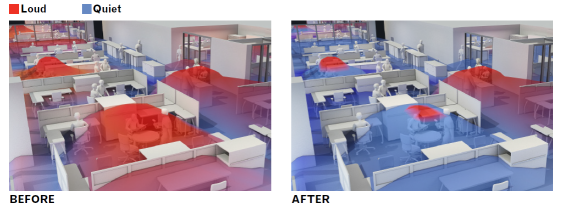

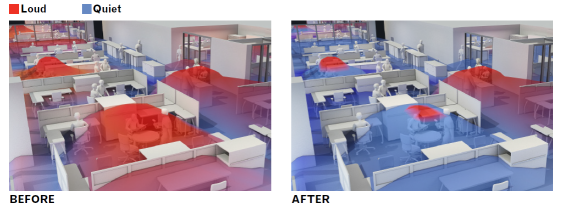

Workspace acoustical features before and after mitigation strategies (GSA Sound Matters)

Acoustical zoning supports both workers that need concentrative quietness to complete tasks and those in need of vocal interaction. Separate noise generating activities, such as conference rooms, away from work that needs a quieter environment and provide specialized areas for conversations demanding privacy to occur.

Blocking sound waves prevents noise from traveling to undesired ears but requires more than simply blocking line of site. For example, research shows that higher cubicle partitions provide small amounts of additional acoustical shielding. But this increase in ‘visual privacy’ may encourage people to talk louder because they believe they have more privacy. As a result this could lead to even more disruptions.

Masking strategies "cover" the unwanted sound by providing a low and uniform level of background noise to contrast sporadic and distracting interruptions to the quiet workplace. Often perfect silence can be distracting in the working environment. Sound masking technologies may be electronic, with speakers providing artificial white noise, or part of a well-planned ductwork and diffuser system.

An effective daylighting strategy sufficiently illuminates the building space without subjecting occupants to inconvenient glare or light level fluctuations. Daylight can be reflected into the interior of the space using light shelves at the building’s perimeter or light tubes from the roof. Daylighting reduces the overall lighting energy consumption and provides a visually stimulating and productive environment for occupants.

Supplementing natural light with a combination of direct and indirect light sources creates a consistent and well dispersed indoor lighting level for occupants to complete visual tasks. Potentially irritating glare should be avoided along with overbearing shadows on the walls and ceiling. Personal controllability and integration of task lights should be part of a successful lighting strategy.

Views to the outdoors provide building occupants with not only natural daylight but a visual connection to the environment. This visual connection has demonstrated increased morale in workers over the period of a work day and is an important part of a comprehensive indoor environmental strategy.1 Locating private office spaces away from the building envelope, implementing lower partitions, and providing open office space adjacent to exterior-facing windows are all strategies to optimize views for building occupants. However, employing these strategies to increase views must be balanced with acoustical and HVAC zoning objectives.

1. DOE LBL | IAQ Science Findings Resource Bank - Daylight, View, and School and Office Work Performance

Incorporating task lights into the overall lighting strategy allows occupants to customize their ambient light conditions on a personalized basis. Task lights can be hard-wired into a cubicle / desk or come simply in the form of a desk lamp. All automated controls, including occupancy sensors, should allow for occupant override. Occupants should also be given control over natural light levels through effective, adjustable shading.

Modern office policies and technologies enable mobility as a means for the occupant to seek out desirable environmental conditions. Mobile laptops and Wi-Fi internet allow users to take work to more conducive areas for their task at hand, including the exterior of the building. Distracting acoustics can be avoided altogether by simply moving location. Consider corporate telecommuting programs that incentivize occupants for working in more beneficial areas. Mobility further increases individual control, which is essential to high indoor environmental quality.