Building Energy Security and Efficiency

Energy is fundamental to the services and amenities we expect from buildings. Effective building operations and management (O&M) requires managing energy use and supply based on a range of critical objectives, including:

- Mission assurance, continuity of services, and facility flexibility and resilience.

- Using energy efficiently to minimize waste and taxpayer-funded costs throughout each building’s lifecycle.

- Supporting the longevity, resilience, and reliability of the electric grid.

- Safeguarding U.S. energy independence and autonomy.

- Promoting clean air, clean water, and healthy communities.

- Supporting innovative American-made technologies.

21st-century building energy management presents complex challenges that require understanding interconnected building and energy supply systems, like the electricity grid. Tools like building automation systems can greatly enhance O&M effectiveness when properly deployed and used.

Building Energy Security and Efficiency Strategies

- Energy Efficiency: reducing energy use through more efficient technologies and operational approaches.

- Use energy audits to identify facility-specific needs and opportunities. Factor in evolving energy needs, such as potential electricity use for vehicle charging. Consider the service life, replacement cycle and pollution impacts of systems and equipment. Purchase and install efficient, ENERGY STAR certified equipment.

- Maximize energy efficiency before applying other strategies. Less energy used means less energy purchased. It can also save money upfront, for example, by capitalizing on daylight to reduce lighting installation costs and by allowing right-sized, lower-cost HVAC equipment.

- System Modernization: System Modernization: replacing legacy HVAC and other building equipment with significantly more efficient systems, such as heat pumps.

- Building and Grid Integration: improving the integration of buildings with the electric grid to manage energy costs and facilitate the transition of the grid to cleaner, more resilient and more efficient operations.

- As building systems are designed or updated, consider enhancing building controls and grid interactivity to reduce energy use, costs, and pollution impacts while increasing resilience. For example, participate in load-management activities such as peak shaving and demand-response that can shed loads at peak demand times. These programs can provide revenue or savings, while improving grid reliability and air quality. For more information, see SFTool’s Grid-Interactive Efficient Buildings page.

Building Energy Security and Efficiency Components

- Whole Building

Energy Efficiency

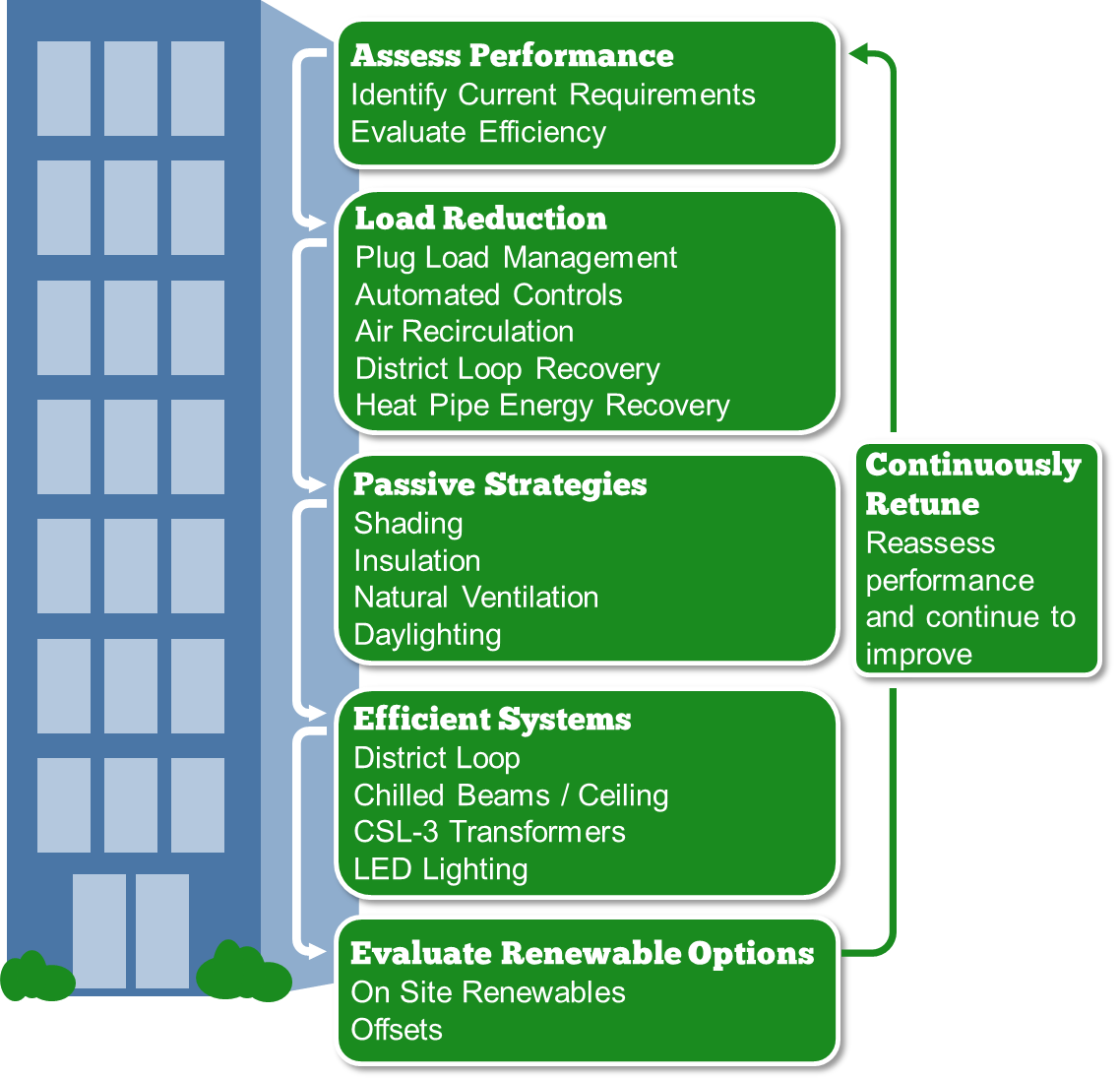

The first step a building professional should take to improve energy management is maximizing the building’s energy efficiency. This critical step saves money, reduces the amount of energy and hence size and cost of equipment that is needed, and makes future energy management strategies easier and often less expensive to deploy. Some of the most effective efficiency measures are passive, i.e., a product of the building’s siting and structure, including constructing a building envelope that is air-tight and has thermal mass capable of absorbing heat from sunlight during the heating season and heat from warm air during the cooling season. Properly orienting the building to make optimal use of the sun’s warmth, light and energy-producing capability has a big impact on how much energy is consumed.

Active efficiency measures are those that involve designing and operating building systems and equipment to perform more efficiently. Among building systems, space heating accounted for close to one-third of end-use consumption in U.S. commercial buildings in 2018.1 Other energy-intensive building systems include ventilation, lighting, cooling and water heating. There are an ever-increasing number of technologies and strategies to optimize the efficiency of all of these systems, as well as building controls and energy management systems to ensure they all work together as efficiently as possible.

In addition to building systems, a building professional must be aware of plug loads, the often increasing amount of energy used by plugged-in equipment, from computers to video screens, and process loads, the energy used by systems hardwired into a building structure, such as elevators, enterprise servers, and commercial kitchen equipment. Plug loads are projected![]() to continue to be one of the fastest-growing uses of energy in buildings in the coming decades.

to continue to be one of the fastest-growing uses of energy in buildings in the coming decades.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Association

Energy Efficiency in Building Systems

For all building equipment and fixtures, opt for ENERGY STAR certified products![]() and/or FEMP designated products

and/or FEMP designated products![]() wherever possible. In addition, SFTool's Cost-Effective Upgrades tool provides specific building efficiency opportunities geared to building size and climate zone.

wherever possible. In addition, SFTool's Cost-Effective Upgrades tool provides specific building efficiency opportunities geared to building size and climate zone.

Energy Efficiency Strategies

Energy efficiency is a complex topic because it involves optimization and interaction among multiple building systems. Upgrades and replacements must also be planned and conducted thoughtfully to avoid negative impacts on occupant health, comfort or job performance.

Renewable Energy

Renewable energy comes from sources that are either inexhaustible or can be replaced very rapidly through natural processes. Examples include the sun, wind, geothermal energy, small (river-turbine) hydropower, and other hydrokinetic energy (waves and tides).

Using energy generated from renewable sources has a range of benefits. It mitigates pollutant emissions, reduces U.S. dependence on foreign energy sources, and onsite renewable energy increases Federal energy security by reducing facility reliance on an electricity grid. Renewable energy tends to provide long-term price stability, as it doesn’t depend on costly and/or price-variable fuel sources. At the same time, some renewable energy sources, such as sun and wind, are ‘variable’ or ‘intermittent’, meaning the supply is not consistent. There also may be a mismatch between when and where renewable energy is most efficiently produced vs. where and when it is needed most. These challenges can be addressed through Energy Storage/Batteries and Building and Grid Integration.

System Modernization

HVAC systems are typically the biggest users of energy in public and commercial buildings. According to the DOE’s Commercial Building Energy Consumption Survey (CBECs)![]() , in 2018, space heating constituted at least two-thirds of commercial building consumption for natural gas, district heat, and fuel oil. The next most common uses, depending on building type, are domestic water heating and cooking.

, in 2018, space heating constituted at least two-thirds of commercial building consumption for natural gas, district heat, and fuel oil. The next most common uses, depending on building type, are domestic water heating and cooking.

HVAC Systems

For the upgrade of HVAC systems to more efficient models, heat pumps![]() are a popular solution. These systems use electricity to transfer heat rather than generate it and are classified by their thermal energy source. Air-source heat pumps work by drawing thermal energy from the air, while geothermal or ground-source heat pumps rely on the relatively constant temperature underground (tapped by geothermal wells), and water-source heat pumps employ a water source. Heat pumps are also characterized by their thermal distribution method, e.g., air-to-air heat pumps use air to circulate heat throughout a building, while air-to-water (hydronic) heat pumps use water for circulation purposes. Variable refrigerant flow (VRF) systems use refrigerants as the circulating medium.

are a popular solution. These systems use electricity to transfer heat rather than generate it and are classified by their thermal energy source. Air-source heat pumps work by drawing thermal energy from the air, while geothermal or ground-source heat pumps rely on the relatively constant temperature underground (tapped by geothermal wells), and water-source heat pumps employ a water source. Heat pumps are also characterized by their thermal distribution method, e.g., air-to-air heat pumps use air to circulate heat throughout a building, while air-to-water (hydronic) heat pumps use water for circulation purposes. Variable refrigerant flow (VRF) systems use refrigerants as the circulating medium.

While air-source heat pump performance has traditionally been diminished in the coldest climates, cold climate heat pump performance continues to improve. HVAC systems typical for large buildings, including those relying on boilers and distributed heating systems, can make cost-effective system modernization challenging. For a short-form training focused on air-source heat pumps, see DOE's Energy-Efficient Product Procurement Training for Federal Agencies![]() .

.

Domestic Water Heating Systems

Consider upgrading domestic water heating systems: heat pump hot water heaters use a third or less energy than traditional electric water heaters since they transfer heat instead of generating it.

Building Performance Standards

An increasing number of local and state governments are starting to adopt building performance standards, which are outcome-based policies aimed at reducing the emissions of the built environment by requiring existing buildings to meet energy performance targets. The National Building Performance Standards Coalition![]() brings these jurisdictions together to learn from each other.

brings these jurisdictions together to learn from each other.

Energy.gov | Better Buildings Initiative ![]()

Building and Grid Integration

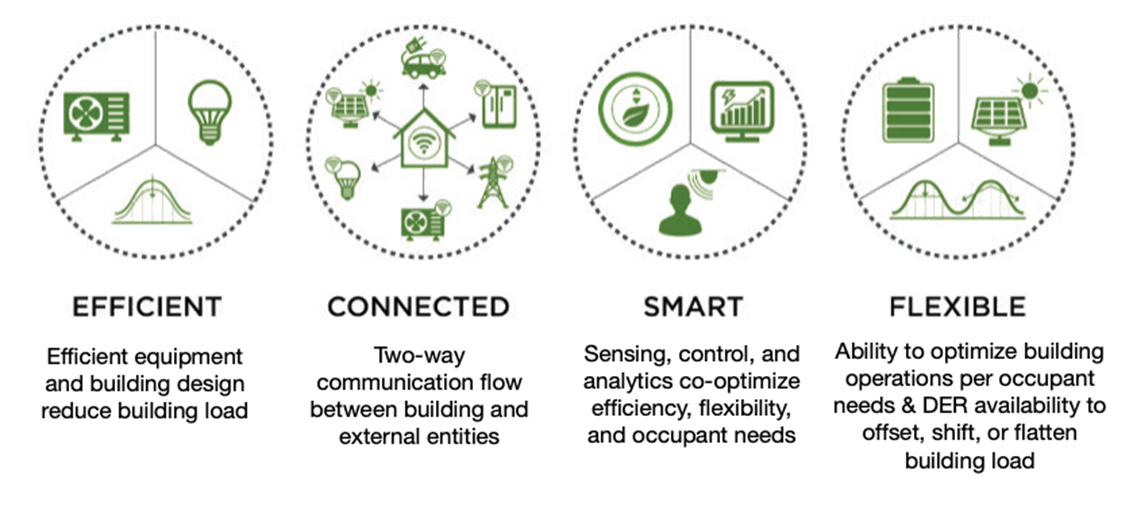

DOE’s Building Technologies Office coined the term Grid-Interactive Efficient Buildings (GEBs)![]() , uniting the goals of building energy efficiency and building and grid integration into one suite of strategies. GEBs build on the well-established discipline of energy efficiency by adding strategies and technologies to also manage peak demand and coordinate buildings’ electrical loads, taking into account peak usage hours, generation mix, storage options, and resiliency needs as appropriate. Efficient appliances, equipment, and whole building energy optimization reduce both overall energy consumption and peak demand.

, uniting the goals of building energy efficiency and building and grid integration into one suite of strategies. GEBs build on the well-established discipline of energy efficiency by adding strategies and technologies to also manage peak demand and coordinate buildings’ electrical loads, taking into account peak usage hours, generation mix, storage options, and resiliency needs as appropriate. Efficient appliances, equipment, and whole building energy optimization reduce both overall energy consumption and peak demand.

For more information, see DOE’s Better Buildings Federal Smart Buildings Accelerator![]() and SFTool’s Grid-Interactive Efficient Buildings page. For a case study showing GSA applying GEB concepts to a building project, see GSA Oklahoma City Federal Building: Smart Buildings Case Study (March 2023)

and SFTool’s Grid-Interactive Efficient Buildings page. For a case study showing GSA applying GEB concepts to a building project, see GSA Oklahoma City Federal Building: Smart Buildings Case Study (March 2023)![]()

Adapted from: Department of Energy EERE GEB Overview

Energy Security and Efficiency Case Studies

Wayne Aspinall Federal Building & U.S. Courthouse , Grand Junction, CO

, Grand Junction, CO

The Wayne Aspinall Federal Building is a case study for minimizing energy use. Originally constructed in 1918, renovations successfully converted the building into a model of energy efficiency, while preserving its original character. Energy objectives are met through a combination of high-performance, energy efficient materials and systems, and on-site renewable energy generation. As a result of the upgrades, the building is now 50% more energy efficient than a typical office building. On-site renewable energy generation is intended to produce 100% of the facility’s energy needs throughout the year. Energy efficiency features include variable refrigerant flow (VRF) for the HVAC, a geo-exchange system, advanced metering and building controls, high-efficient lighting systems, a thermally enhanced building envelope, interior window systems which maintain the historic windows but increase thermal performance, and advanced power strips (APS) with desk mounted individual occupancy sensors. Renewable energy is provided by 385 photovoltaic roof panels that generate enough power to meet the electricity needs of 15 average American homes or 123 kw.

The R.W. Kern Center demonstrates techniques to reduce energy use. In addition to passive solar orientation, an air-tight envelope, and triple-glazed windows to help mitigate against large swings in temperature and humidity, the double-stud cavity wall and roof are filled with cellulose insulation to achieve assembly values of R-40 and R-60, respectively. An inverter-driven heat pump system provides heating and cooling to the spaces, separate from the heat recovery ventilation system. By reducing the building’s design energy use, a 118 kilowatt rooftop solar array can generate more than enough energy on an annual basis. Wood is the major structural material and unnecessary finishes were rejected to conserve funds for high-impact, high-performance components, like the triple-glazed windows and insulation.

Phipps Center for Sustainable Landscapes , Pittsburgh, PA

, Pittsburgh, PA

The Phipps Center for Sustainable Landscapes is a case study for minimizing energy use. Passive-first strategies are coupled with high-performance technologies to permit the downsized mechanical system (a custom-built rooftop energy recovery unit) to operate as efficiently as possible. The long, relatively narrow building sits on an east-west axis, which allows for maximizing southern exposure. High-performance glazing on the north and south facades permits solar gain in the cold months, while louvers and strategic deciduous tree plantings prevent unwanted heat gain and glare in the warm months. Computational fluid dynamics studies determined placement for BAS- and occupant-controlled windows to maximize natural ventilation. Daylighting is maximized with light shelves and sloped ceilings to direct natural light into the interior and energy use is monitored by the individual plug, which permits any anomalies to be addressed. Occupants each have electricity meters at their desks to encourage energy-saving behaviors. Energy is produced onsite via a vertical-axis wind turbine and a 125kW photovoltaic array. The atrium, constructed of concrete with recycled fly ash, acts as thermal mass, increasing energy efficiency.

The Chesapeake Bay Brook Environmental Center , Virginia Beach, VA

, Virginia Beach, VA

The Chesapeake Bay Brook Environmental Center is a case study for minimizing energy use. Conservation strategies were organized into passive and active approaches. The building was designed to maximize diffused daylighting from the north while shielding the building interior from direct sunlight from the south and a photosensor dimming-control system was used in almost every space to reduce electric lighting when sufficient daylight is present. Windows and even walls were designed to open up and take advantage of the natural breezes prevalent near the Chesapeake Bay and the mechanical system uses a variable-refrigerant flow (VRF) system with geothermal wells. Two 10-kW wind turbines, each on a 70-ft pole, are located off the east and west ends of the building, as far away as possible from nearby trees, but close enough to limit site disturbances. A PV system, consisting of (141) 270-W modules for a total of 40 kWp (kilowatt peak), is located on the sloped roof and 6.5 kW of additional PV modules were added after the completion of construction.

Tools

Auditing, Estimating and Data Analysis Tools

- Audit Template (energy.gov)

- a web-based tool for entering building energy audit data, performing data validation, exporting data in various formats, and submitting data to cities that have local energy audit ordinances.

- a web-based tool for entering building energy audit data, performing data validation, exporting data in various formats, and submitting data to cities that have local energy audit ordinances. - BETTER (Building Efficiency Targeting Tool for Energy Retrofits) (LBL.gov)

- a software toolkit that enables building operators to quickly and easily identify the most cost-saving energy efficiency measures in buildings and portfolios using readily available building and energy data.

- a software toolkit that enables building operators to quickly and easily identify the most cost-saving energy efficiency measures in buildings and portfolios using readily available building and energy data. - ENERGY STAR Portfolio Manager Target Finder

- an interactive resource management tool that enables users to benchmark the energy use of any type of building by comparing a building’s energy performance to similar buildings nationwide, normalized for weather and operating characteristics.

- an interactive resource management tool that enables users to benchmark the energy use of any type of building by comparing a building’s energy performance to similar buildings nationwide, normalized for weather and operating characteristics. - Standard Energy Efficiency Data (SEED) Platform (energy.gov)

- an open-source software application designed to manage building performance data (such as required by a benchmarking ordinance).

- an open-source software application designed to manage building performance data (such as required by a benchmarking ordinance). - CBES Pro (LBL.gov)

- a set of program and technical products aimed at small commercial buildings (< 50,000 sq. ft.) It provides user configurable retrofit analysis using real-time EnergyPlus simulations.

- a set of program and technical products aimed at small commercial buildings (< 50,000 sq. ft.) It provides user configurable retrofit analysis using real-time EnergyPlus simulations. - Water Project Screening Tool (energy.gov)

- an Excel-based tool enabling federal agencies to quickly screen sites for water efficiency opportunities.

- an Excel-based tool enabling federal agencies to quickly screen sites for water efficiency opportunities. - Zero Tool

- a web-based tool that enables users to develop energy baselines and reduction targets for new and existing buildings.

- a web-based tool that enables users to develop energy baselines and reduction targets for new and existing buildings.

Procurement Tools

- Energy Savings Performance Contract ENABLE for Federal Projects (energy.gov)

- a set of pre-established procurement and technical tools to administer projects through the GSA Supply Schedule SIN 334512

- a set of pre-established procurement and technical tools to administer projects through the GSA Supply Schedule SIN 334512 .

.

Building and Operational Performance Tools

- Integrated Systems Packages (LBL.gov Building Technology & Urban Systems Division)

- toolkits, including efficiency measures that are commercially proven and amenable to standardization, designed for three real estate events: tenant fit-out, rooftop unit replacement and whole building renovation.

- toolkits, including efficiency measures that are commercially proven and amenable to standardization, designed for three real estate events: tenant fit-out, rooftop unit replacement and whole building renovation. - PNNL Building Re-tuning

- an online interactive training curriculum and resources for building operators and managers, as well as energy service providers, of both large (>100,000 sq. ft.) and small (<100,000 sq. ft.) to identify and correct no- and low-cost operational problems that plague commercial buildings.

- an online interactive training curriculum and resources for building operators and managers, as well as energy service providers, of both large (>100,000 sq. ft.) and small (<100,000 sq. ft.) to identify and correct no- and low-cost operational problems that plague commercial buildings. - Healthy Buildings Toolkit (PNNL.gov)

- a toolkit to facilitate building-wide integrated upgrades and operational improvements, leveraging savings from increased productivity to enhance business cases for the implementation of energy-conservation measures.

- a toolkit to facilitate building-wide integrated upgrades and operational improvements, leveraging savings from increased productivity to enhance business cases for the implementation of energy-conservation measures. - REopt Energy Integration & Optimization Home (NREL.gov)

- a techno-economic decision support platform to optimize energy systems for buildings, campuses, communities, and microgrids.

- a techno-economic decision support platform to optimize energy systems for buildings, campuses, communities, and microgrids. - CARE Tool - Carbon Avoided: Retrofit Estimator

- allows users to compare the total carbon impacts of renovating an existing building vs. replacing it with a new one.

- allows users to compare the total carbon impacts of renovating an existing building vs. replacing it with a new one. - Smart Energy Analytics Campaign Toolkit (DOE Better Buildings Program)

- a toolkit to help facility owners and managers take advantage of savings opportunities and performance improvements from EMIS and ongoing monitoring practices.

- a toolkit to help facility owners and managers take advantage of savings opportunities and performance improvements from EMIS and ongoing monitoring practices. - Low Carbon Technology Strategies Toolkit (DOE Better Buildings Program)

- a toolkit to aid owners and operators of existing buildings in planning retrofit and operational strategies to achieve deep carbon reductions.

- a toolkit to aid owners and operators of existing buildings in planning retrofit and operational strategies to achieve deep carbon reductions.

Resources

- GSA.gov | Green Building Advisory Committee Advice Letter: Recommendations for Advancing GHG Reductions in Existing Federal Buildings - Appendix C

- Energy.gov | Carbon Pollution-Free Electricity Resources for Federal Agencies

- Energy.gov | Energy 101 Video: Energy Efficient Commercial Buildings

- DOE Better Buildings Program | Better Climate Challenge

- Decarbonization | Better Buildings Initiative

- HVACResourceMap.net | HVAC Resource Map Commercial HVAC

- Energy.gov | EMIS Primer Second Edition

- EnergyStar.gov | Commercial Buildings

- DOE Better Buildings Program | Federal Smart Buildings Accelerator

- Energy.gov | Metering in Federal Buildings

- Energy.gov | Commissioning in Federal Buildings

- Energy.gov | Decarbonizing HVAC and Water Heating in Commercial Buildings

- Energy.gov | GHG Emissions Reduction Audit Checklist

- Better Buildings Initiative | GHG Emissions Reduction Audit Scope of Work Template

- Energy.gov | Grid-Interactive Efficient Buildings

- RMI.org | Medium-Size Commercial Retrofits

- New Buildings Institute | An insider's guide to talking about carbon neutral buildings

1. EIA.gov | 2018 Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey, Consumption and Expenditures Highlights