Conducting a Life Cycle Assessment

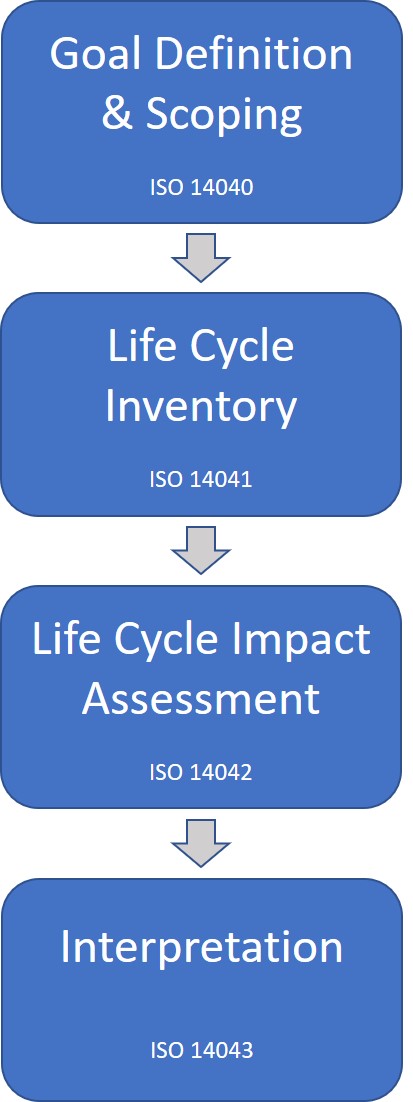

The LCA process is a systematic, phased approach and consists of four components:

1. Goal Definition and Scoping

Define and describe the product, process, or activity. Establish the context in which the assessment is to be made and identify the system boundaries![]() , the functional units

, the functional units![]() , any assumptions and limitations, as well as the impact categories

, any assumptions and limitations, as well as the impact categories![]() (environmental effects) that will be considered for the assessment. These decisions are unique to each project as each project team’s priorities may be different.

(environmental effects) that will be considered for the assessment. These decisions are unique to each project as each project team’s priorities may be different.

2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Analysis

Create an inventory of flows between the system and the environment across the defined system boundary. Then quantify these inputs (water, energy, and raw materials) and environmental outputs (e.g. air emissions, solid wastes, water effluents). For an example of a U.S. data repository see the Federal LCA Commons![]() .

.

3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

Assess the potential human and ecological effects of energy, water, and materials usage and the environmental releases identified in the inventory analysis. Convert flows![]() into equivalent units using LCIA tools (e.g, SimaPro, GREET), so they can be aggregated into one number per impact category.

into equivalent units using LCIA tools (e.g, SimaPro, GREET), so they can be aggregated into one number per impact category.

4. Interpretation

Summarize the results of the inventory analysis and impact assessment with an understanding of the uncertainty and the assumptions used to generate the results. A key purpose of interpretation is to assess the level of confidence in the final results and communicate them in a fair, complete, and accurate manner. This is accomplished by evaluating the sensitivity of significant data elements in each impact category, assessing the completeness and consistency of the study, and drawing conclusions and recommendations based on a clear understanding of how the LCA was conducted and the results were developed

Life cycle assessments are complex processes requiring a great quantity of input data and analysis. Many tools have been developed to assist in this process and make it easier. Some of the building specific tools can be found in the LCA Tools for Buildings section.

Related Topics

Absolute Greenhouse Gases

Absolute greenhouse gas emissions are the total greenhouse gas emissions without normalization for activity levels and includes any allowable consideration of sequestration.

Sustainability.gov | Federal Greenhouse Gas Accounting and Reporting Guidance![]()

Assessments

Assessments are essential tools for linking science and decision making. They survey, integrate, and synthesize science, within and between scientific disciplines and across sectors and regions.

Source: USGCRP: Assess the U.S. Climate - What are assessments?Carbon Footprint

A Carbon Footprint is the amount of greenhouse gas emissions (in units equivalent to carbon dioxide emissions) emitted by an entity, be it a person, building, company, or country.

Conducting LCA

Construction

Embodied Energy

A measure of the energy used to harvest, manufacture, process, bring to market, and dispose of a product. In Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) of building materials, embodied energy helps identify the true energy cost of an item. This accounting method attempts to quantify the fossil fuels, nuclear energy, and other forms of energy that are involved over the material's life.

Energy Performance

Assessing a building’s energy performance involves comparing its energy use to that of peers or a standard. The ENERGY STAR program provides recognized benchmarks for assessing a building’s energy performance.

Environmentally Preferable Products (EPP) and Services

These products and services are less harmful to the environment than their standard counterparts. See: EPA | About the Environmentally Preferable Purchasing Program![]()

Green Building

High-performance buildings exhibit environmentally responsible intent and perform in a resource efficient manner. They meet the needs of the occupants that live and work in them in a way that minimizes demand for natural resources and reduces or eliminates waste. High-performance buildings save energy, water, materials, protect the indoor environment and are designed to evolve as occupant needs change. Such buildings are generally more comfortable, healthy, durable and adaptable over time.

Greenhouse Gases

Gases that trap heat in the earth’s atmosphere are called greenhouse gases. Examples of greenhouse gases include carbon dioxide![]() , methane, and chlorofluorocarbons. The primary source of carbon dioxide emissions is the combustion of fossil fuels for energy.

, methane, and chlorofluorocarbons. The primary source of carbon dioxide emissions is the combustion of fossil fuels for energy.

EPA | Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions![]()

FEMP | Annual Greenhouse Gas and Sustainability Data Report![]()

Greenhouse Gases (GHG)

A range of human activities cause the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere (e.g., the release of carbon dioxide during fuel combustion). These gasses can damage or be trapped in the earth’s atmospheric layers, contributing to global climate change.

EPA | Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions![]()

Healthy Buildings

Health, as defined by World Health Organization in its 1948 constitution, is “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. This definition of health has been expanded in recent years to include (1) resilience and the ability to cope with health problems and (2) the capacity to return to an equilibrium state after health challenges.

These three health domains - physical, psychological, and social - are not mutually exclusive but rather interact to create a sense of health that changes over time and place. The challenge for building design and operations is to identify cost-effective ways to eliminate health risks while also providing positive physical, psychological, and social supports as well as coping resources.

Learn more about Buildings and Health.

Life Cycle Cost Assessment (LCCA)

Materials and resources all have environmental, social and economic impacts beyond their use in a project. Impacts occur during harvest or extraction of raw materials, manufacturing, packaging, transporting, installing, use, and end-of-life disposal, reuse, or recycling. These “cradle to cradle” impacts should be considered when purchasing materials. The formal study of this process is known as Environmental Life Cycle Assessment (LCA).

Similarly, Life Cycle Cost Assessment examines the costs and savings throughout the life cycle of a building material. For example, energy efficient equipment and appliances can be more expensive when initially purchased but will save energy (and money) throughout the life of the project. Therefore, it may make sense to invest in more efficient equipment that costs more up front but saves money and energy over time.

The Sustainable Facilities Tool allows you to compare life cycle costs for materials, as well as other environmental criteria, by following the green dots and clicking "compare materials" in Explore Sustainable Workspaces.

Also, check out information on LCA at the Whole Building Design Guide:

WBDG | Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA)![]()

Net Zero Energy Building

A building that is designed, constructed, and operated to produce as much energy as it uses over the course of a year. Net Zero Energy Buildings combine exemplary building design to minimize energy requirements with renewable energy systems that meet these reduced energy needs.

See the Net Zero Energy section for more information!

Sustainability

Sustainability and sustainable mean to create and maintain conditions, under which humans and nature can exist inproductive harmony, that permit fulfilling the social, economic,and other requirements of present and future generations.

Whole Building Systems Thinking

Unlike conventional design processes, where components and disciplines are treated separately, sustainable design requires an evaluation of whole systems. When retrofitting an office, consider the space as a whole. This means thinking not only about the lighting, the flooring, the windows, the HVAC system, and the furniture as separate components, but also thinking about the relationship between each of these components and the ways that those relationships create the space, and how that fits with sustainability goals.

Check out the Whole Building Systems section in Explore for information on building systems, their relationship to one another, and the integrated design team necessary to reach sustainability goals.

For example, if a project’s goal is to save energy from lighting and improve occupant comfort, it should think not only about the type of lighting fixtures needed, but also how the space will be used by the occupants, the amount of sunlight streaming through the windows at different times of year, how that light gets bounced into the space, how the light levels are controlled, and even the colors of the walls. By thinking holistically about the lighting system, rather than simply about the lighting components, a more comfortable, efficient, healthy and productive space can be created. In addition, the project “system” is nested within larger systems, such as a watershed, an air shed, a forest, a neighborhood and city, and so forth; these larger systems should also be considered.